Is learning to read earlier better?

We live in a competitive society that rewards being first and best — and this mentality is deeply ingrained in most of us. No matter how often we tell ourselves that each child is unique and will grow at their own pace, it’s natural for us to feel proud and excited when our children hit milestones “early” or excel in certain areas — and to feel concerned when our kids are “late.”

Pressure to read early

Learning to read is possibly the most significant academic benchmark of childhood. Unfortunately, the expected timing of obtaining this skill has crept earlier and earlier over the last 10 years. In response to Common Core kindergarten guidelines, which went into effect in 2009, the public education system in the United States has been putting more and more pressure on kids to perform academic skills, like reading, earlier. The study titled “Is Kindergarten the New First Grade?” compared kindergarten teachers’ attitudes nationwide in 1998 and 2010, and found that the percentage of teachers expecting children to know how to read by the end of the year had risen from 30 to 80 percent.

In response, teaching methods have changed, with teachers of even prekindergarten students expecting children to spend extended periods of time doing seated work, like phonics worksheets, independently. There’s the thought that if we want them to read younger, we need to teach them how to read earlier using this “direct instruction” approach.

Why this doesn’t really work

Direct instruction, however, isn’t the best way to teach young children to read, because learning to read is like baking a cake. When you bake a cake, you need to combine ingredients — eggs from the fridge, flour from the pantry, and so on. But the thing is, those eggs didn’t miraculously appear in your fridge. They came from your store, and before that from a packaging facility, and before that from a chicken. In other words, there were a lot of steps that needed to happen before you could even reach for those ingredients to mix them up and bake them.

Reading is the same way. The act of reading is made up of a huge number of foundational skills — some very sophisticated — that develop with time and practice, and include far more than recognizing alphabet letters and sounds. Learning to hear and manipulate sounds, sustaining attention, remembering information, thinking abstractly — these are skills that cannot be taught through direct instruction alone. In order for a child to learn reading in the true sense — to be able to use reading as a means for obtaining, interpreting and evaluating information — we cannot skip steps. Can some young children learn how to sound out words? Sure. But more often than not, these children cannot meaningfully understand what they are reading. They are not set up for long-term reading success.

The act of reading is made up of a huge number of foundational skills that develop with time and practice.

Research bears this out. Studies show that by fourth grade, children who were reading at age 4 were not significantly better at reading than their classmates who’d learned to read at age 7. What’s more, in Finland and Sweden, kids don’t even start formal schooling until they are 7 years old. Yet, Finnish and Swedish teenagers outperform American teens in international tests of reading, math and science.

A better way to learn

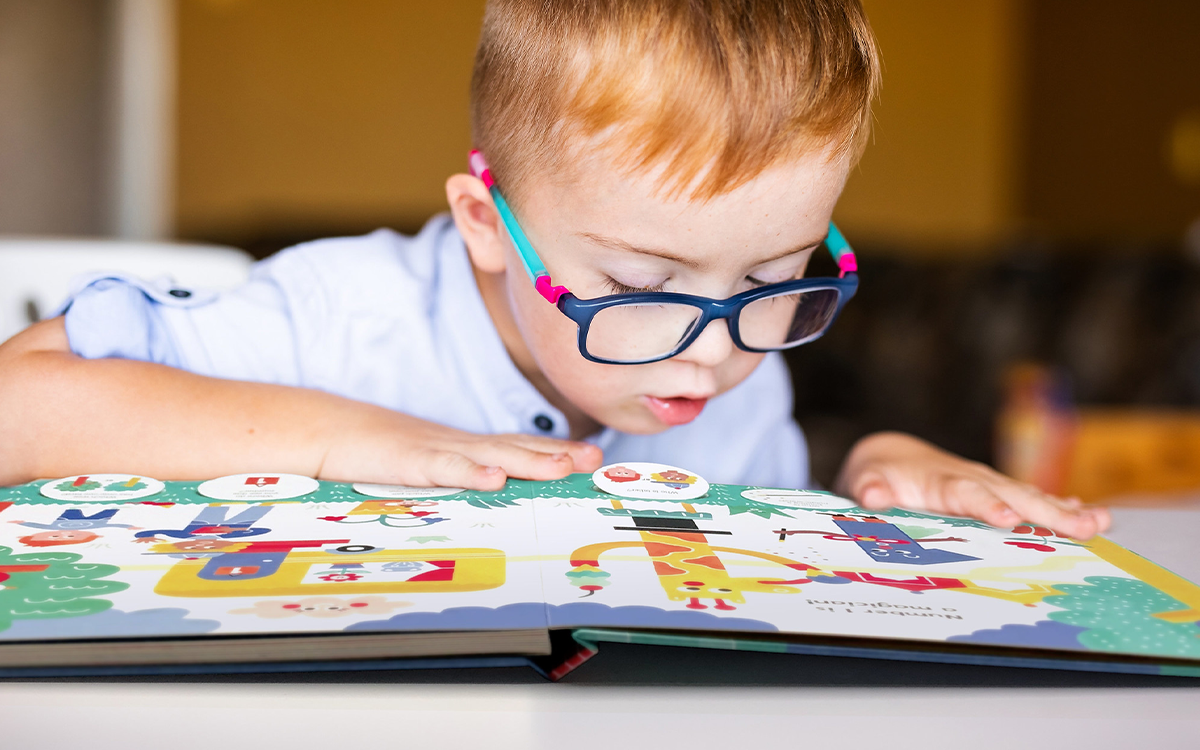

If you have an early reader, it’s totally okay to feel proud and to want to encourage this budding skill. And if you have a preschooler who’s not too interested in phonics, don’t despair! Whether your child is an early reader or not, the ideal method for teaching reading is fun and free from pressure. The best way to develop the foundational literacy skills children need is to read aloud to them often, from birth – and to make these experiences joyful and interactive. Frequent conversations and pretend play also help develop the complex language and cognitive skills necessary for reading and academic success.

Our job is to instill a love of reading at an early age to set our children up for strong literacy skills. Isn't it amazing that the best outcome will come from the most joyful approach?